|

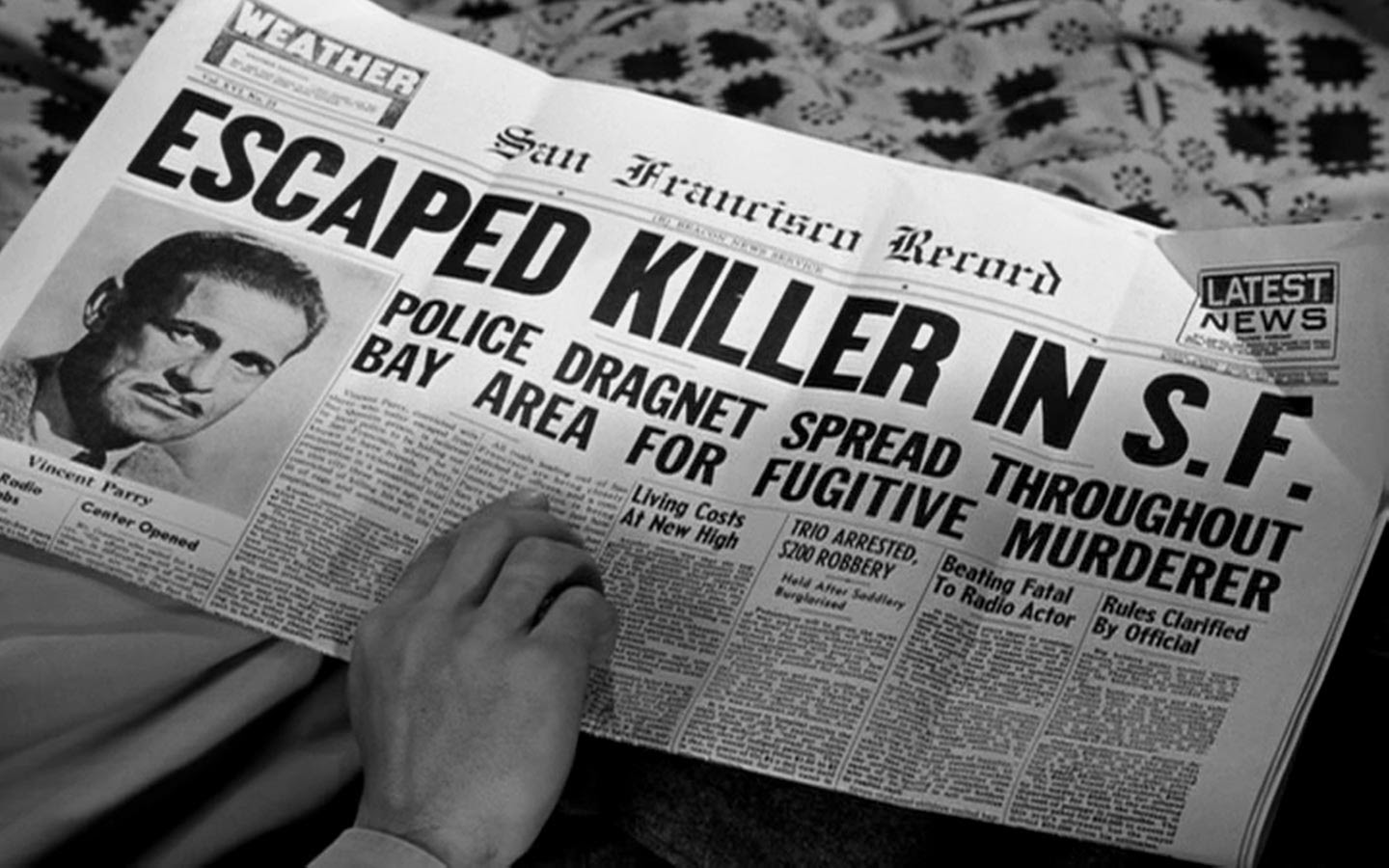

| Dark Passage (1947) |

The first 37 minutes of

Dark Passage (1947) make extensive use of the subjective shot by representing the film's main character almost exclusively through his own point-of-view. Vincent Parry, an escaped criminal convicted of killing his wife, is defined by what he sees. The camera acts as his eyes, so when other characters look at him, they're looking directly at the camera. While not every shot in this part of the film is from Vincent's point-of-view (there are establishing shots, for example, not attached to any character's point of view), with only a few exceptions, Vincent's presence is always indicated this way. What is presented as Vincent's authentic subjectivity, however, is not always what it seems. The film uses a number of techniques to

simulate Vincent's uninterrupted point-of-view while still presenting it as authentic. While some of these methods help to preserve this illusion, others work against it. Here's a look at three sequences in the film that demonstrate this.

The ride with Baker

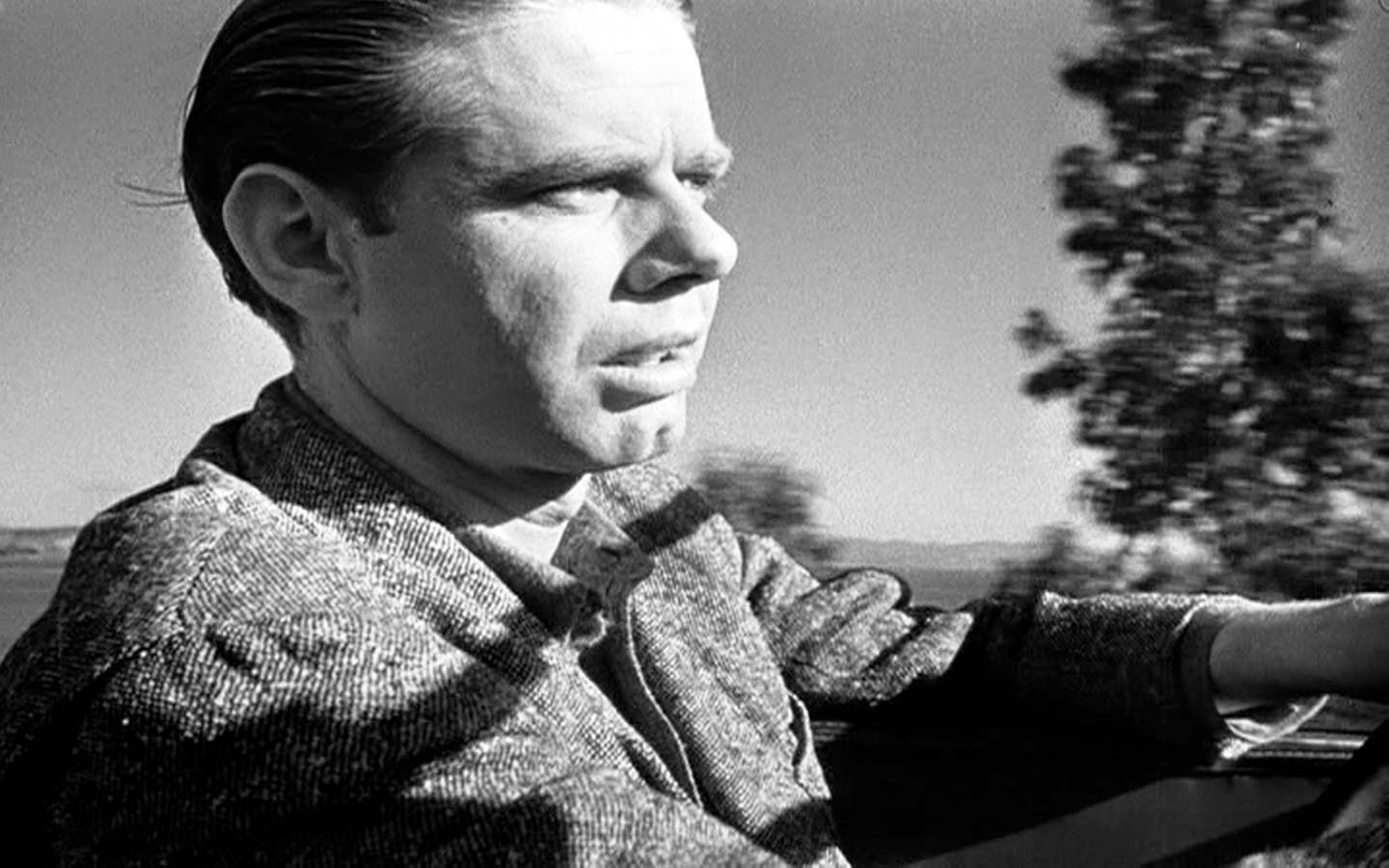

This sequence is actually part of the longer opening scene, which shows the truck leaving San Quentin, Vincent tipping the barrel over the side and rolling down the hill, and his approach to the road. We begin with the last part of the last shot of that action, as Vincent looks to his left (which is also frame left) and considers his options (shot 1).

|

| 1 |

|

|

| 1 pans right, concealing cut |

|

|

| 2A |

|

|

| 2A - Vincent waves |

|

|

| 2B |

|

|

| 2B - movement conceals cut |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 3 moves left, concealing cut |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 4 pans right, dissolves |

|

|

| 5A |

|

|

| 5B |

|

|

| 5C |

|

|

| 5C pans right, concealing cut |

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

| 8 - Baker looks down |

|

|

| 9 |

|

|

| 9 pans left, concealing cut |

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

| 11A |

|

|

| 11B |

|

|

After Vincent looks to his left (frame left), he then turns his head to the right in a rapid pan which conceals a cut to shot 2. In shot 2A, then, he should be looking down the street in the opposite direction from shot 1 and the approaching car should stop in front of him heading frame left. When Baker stops his car, however, it is facing frame right. The rapid pan used to simulate the turn of Vincent's head and to create the illusion of prolonged continuous action

1 has also instantly moved Vincent to the other side of the road. This places Vincent conveniently on the passenger side of the car, but it does so without depicting the crossing of the road.

As Vincent enters Baker's car in shot 2B, camera movement and the car's dark interior conceal the cut to shot 3, of Vincent's muddy shoes, which Baker has just called attention to by asking "How'd you get your feet wet? Been wading?" There is a change in perspective here, as Vincent's shoes are shown in close-up, not in a framing that would accurately represent what he would see when looking down at his feet (compare this to shot 9). The cut to shot 4 is then concealed by a pan left, and Vincent's eyes come to rest on Baker as Baker continues his questioning. This cut also conceals a change from location shooting to sound stage, and for the rest of this shot the car's motion is simulated by rear-screen projection.

A transition back to location shooting is made via a rightward pan and a noticeable dissolve between shots 4 and 5A. It is unclear if this dissolve indicates a passage of time, but the way the conversation overlaps shots 4 and 5 seems to imply that no time has lapsed.

2 This actually makes the dissolve more pronounced, and more of a violation of Vincent's point-of-view — what would such a dissolve, within a point-of-view shot, indicate? Dizziness? A momentary lack of consciousness? Nothing that seems applicable to Vincent at the moment.

During the rest of shot 5, all dialog is spoken off-camera — by Vincent, mostly, but also by Baker as the camera pans left to the back seat, leaving him out of frame as he asks "Where you from?" This allows the conversation to span two shooting locations without the need to synchronize the audio to shots of Baker made at each one. Another rightward pan in shot 5C conceals the cut back to the sound stage, where Baker continues to grill Vincent, in shot 6, about his appearance.

Shot 6 is interesting because it is a longer-than-usual (about 30 seconds) shot of Baker that doesn't do anything to indicate Vincent's discomfort with Baker's questions. The shot is supposed to be Vincent's point-of-view, yet during Baker's grilling, the camera (Vincent's eyes) are fixed unwaveringly on Baker with nothing (like camera movement away from Baker's eyes, for example

3) to simulate Vincent's discomfort but his words. Here we see that while this shot satisfies the requirement of presenting Vincent's point-of-view, it also functions in a way more important to the film by emphasizing what the film wants us to see, regardless of how Vincent would really be seeing it — here, Baker's growing suspicion about Vincent. This choice is perhaps more effective than the alternative of more camera movement — our constant view of Baker scrutinizing Vincent allows us to feel scrutinized as well, so we feel the discomfort Vincent articulates when he demands that Baker stop the car.

4

Before Baker agrees to stop the car, however, a description of Vincent is read over the radio, and the cut to shot 7 — the sequence's first straight cut, not concealed in any way — further emphasizes the importance of Baker's thoughts by framing this shot of the radio from Baker's — not Vincent's — point-of-view. What was supposed to be the continuous presentation of Vincent's point-of-view has now been interrupted by the point-of-view of another character. Like the framing of Vincent's shoes in shot 3, the radio is framed more tightly than it would appear to Baker, but it is shot from the driver's seat position that he occupies, indicating that his reaction to the announcement is more important than Vincent's.

A straight cut to shot 8 returns the camera to Vincent's point-of-view as Baker slows and stops the car to compare Vincent with the description being read over the radio. We see Baker's eyes look up as the announcer describes Vincent's hair, then look down when Vincent's trousers and shoes are described. This downward look is the perfect setup for Baker's eyeline match, but the straight cut to shot 9 gives us a shot of the radio from Vincent's point-of-view instead. While the two previous straight cuts have interrupted Vincent's point-of-view, this is the first that violates it — this cut implies no lapse in time, but certainly a change in perspective. Vincent could not instantly change his perspective this way and would need, as is illustrated by the various rapid pans, to turn his head to do so.

A rapid leftward pan conceals a cut and a return to an outdoor location in shot 10, which shows Baker from a slightly higher angle, indicating, perhaps, that Vincent is no longer sitting. Vincent then punches Baker with hands that swing from behind camera right and left. As Baker falls forward, there is a straight cut to shot 11A, which, though still presented as Vincent's POV, uses a noticeably different framing to show Baker's head hit the steering wheel. Once again, Vincent appears to have instantly changed position without any camera movement to show a transition. Vincent then reaches from behind camera right, takes Baker by the collar, and drags him out of the car and begins to unbutton his jacket in shot 11B.

Irene's apartment

The sequence begins with a dissolve from the previous shot. Unlike the dissolve from the previous example in Baker's car, though, this dissolve does present a lapse in time, however brief, between when Vincent and Irene get out of the elevator and their first moments inside Irene's apartment. Even though this dissolve is between two of Vincent's POV shots, it aids in the a transition of time and place, and is not a violation of a seemingly uninterrupted POV shot.

|

| 1A opening dissolve |

|

|

| 1A |

|

|

| 1B |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

| 2 pans left, conceals cut |

|

|

| 3A |

|

|

| 3B |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

| 6A |

|

|

| 6B |

|

|

| 6C |

|

|

| 6D |

|

|

| 6E |

|

|

| 6F |

|

|

| 6G |

|

|

| 6G dissolve |

|

|

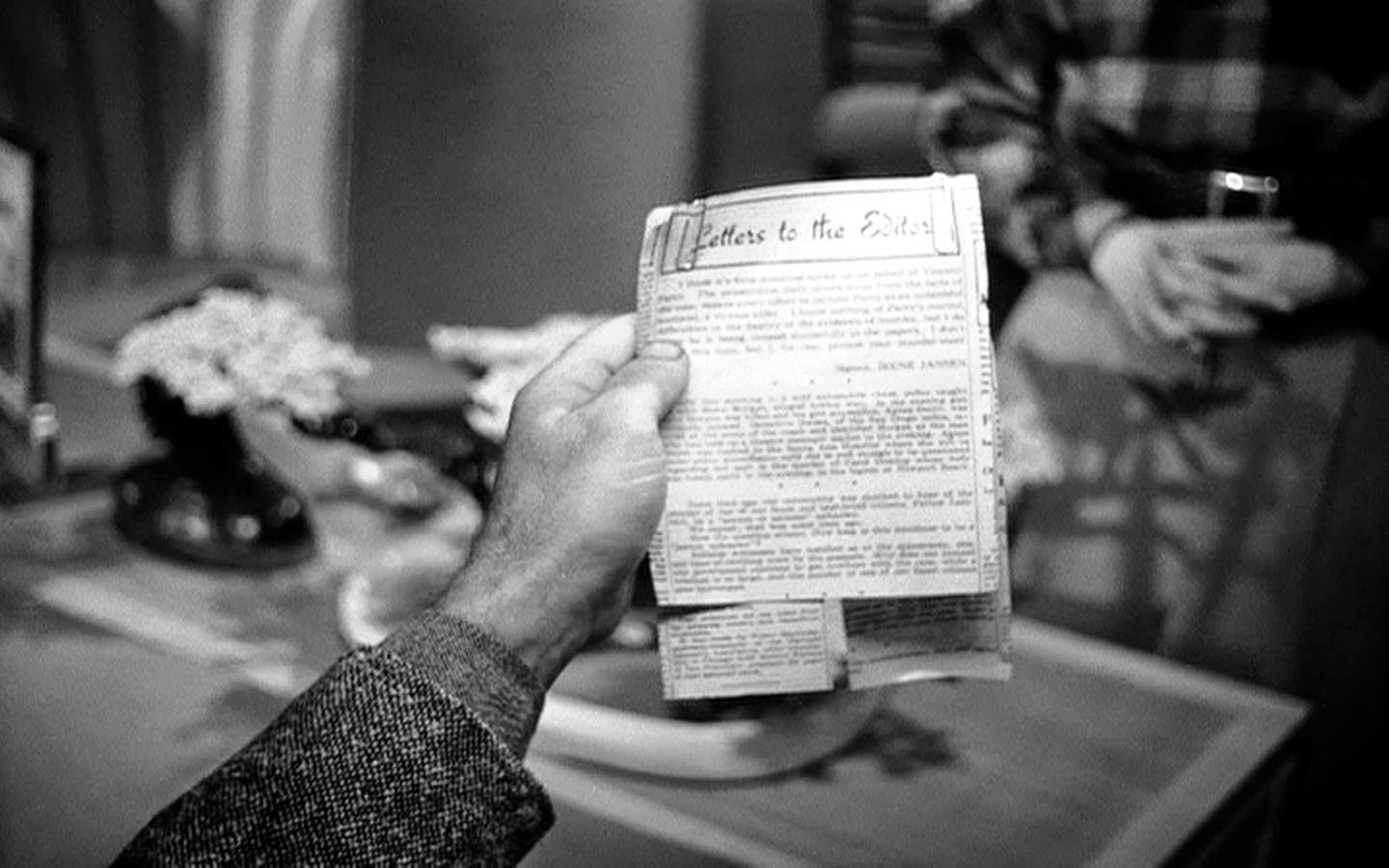

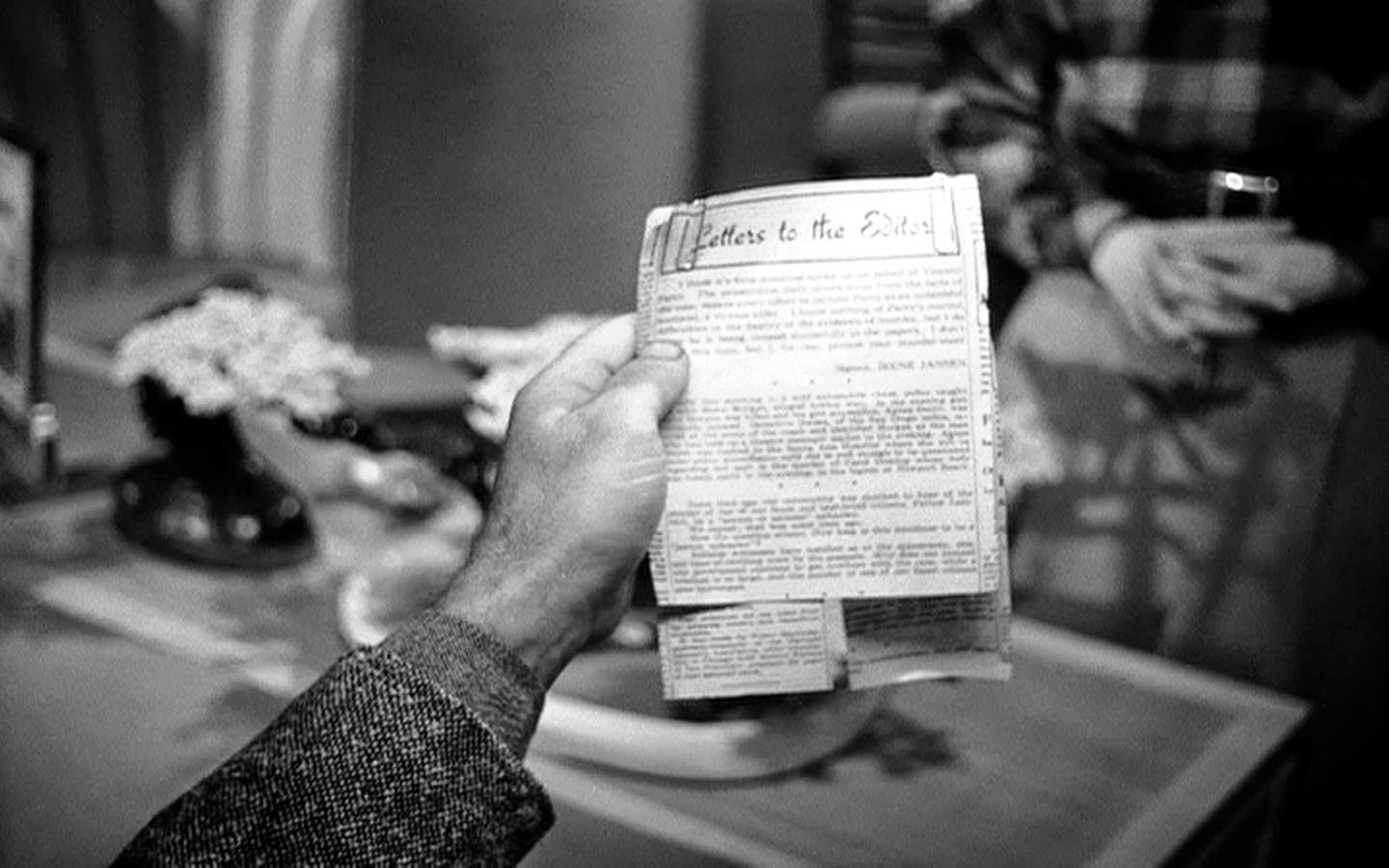

In shot 1B, Vincent's point-of-view follows Irene as she ascends the stairs, the camera movement motivated by her action. She pauses close to the top of the stairs to say, "Turn on the music if you like," motivating a straight cut to shot 2. Immediately after this cut, we hear Irene's final footsteps up the stairs, which appear to aurally continue an action she makes in the very last frames of shot 1B, as she turns her head, ostensibly to continue up the stairs that instant. This would indicate, then, that no time has been omitted between shot 1B and shot 2. Therefore, this cut clearly violates the consistency of Vincent's point-of-view by changing his perspective instantly, without a pan to simulate the movement of his head and eyes to the record player.

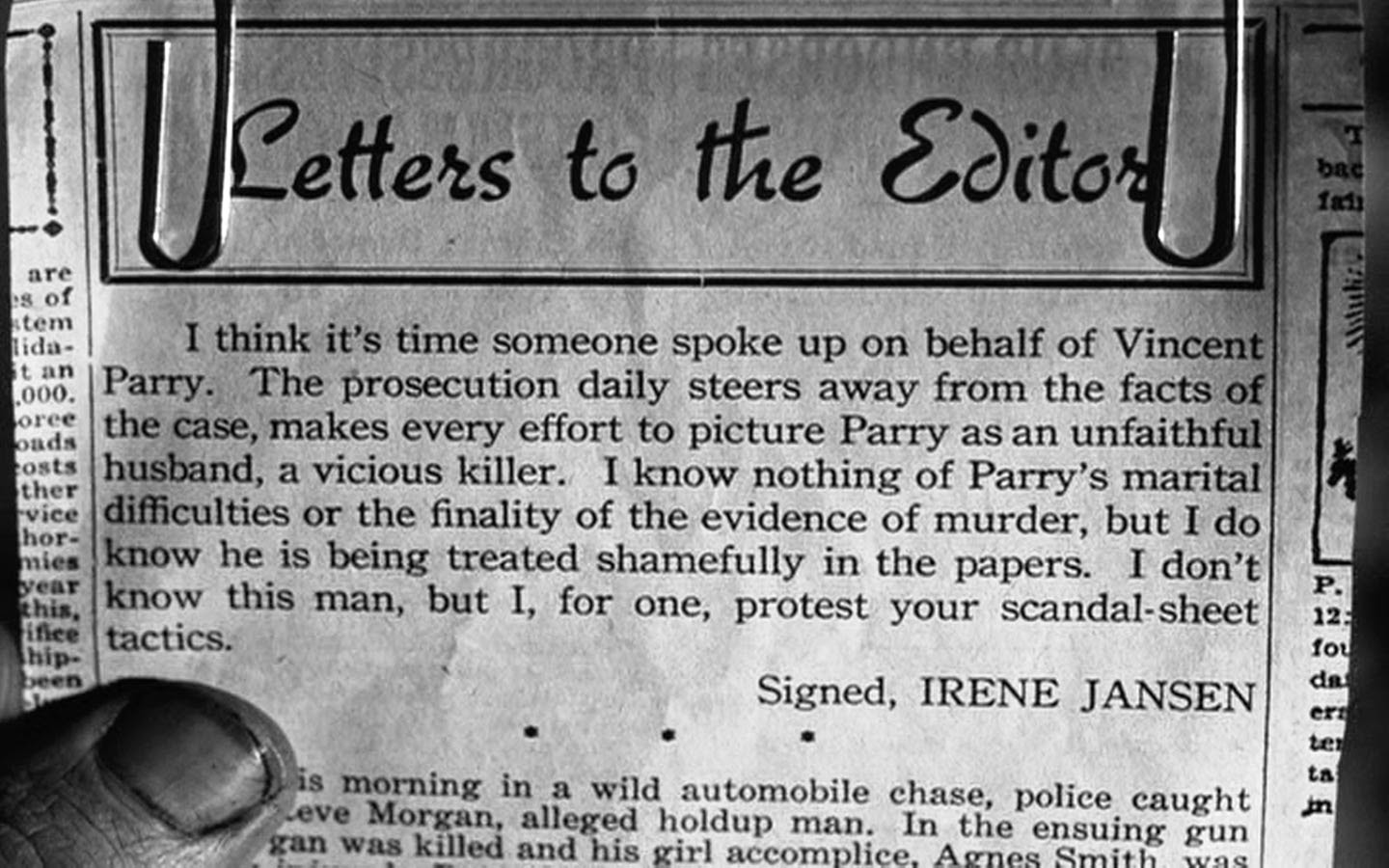

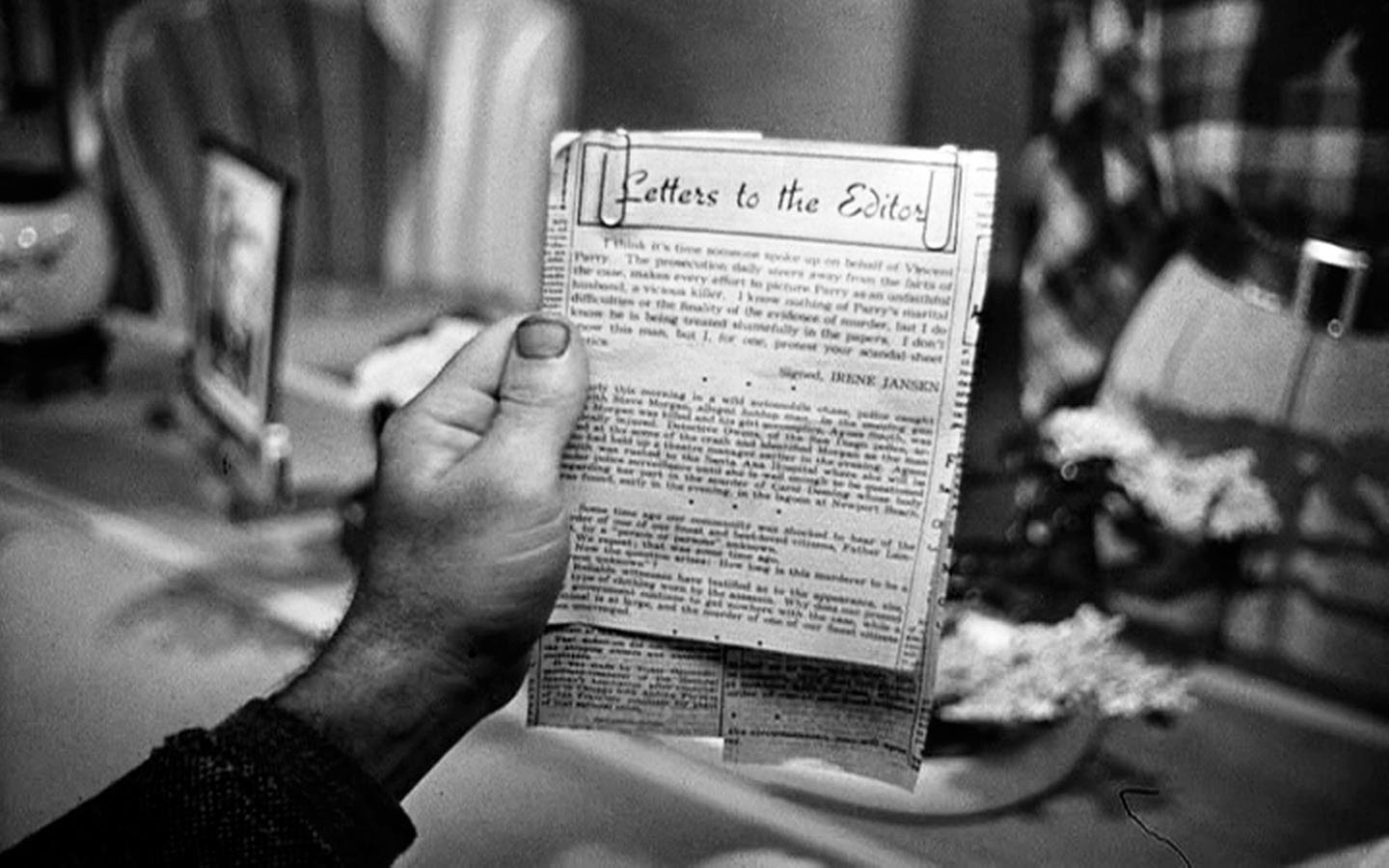

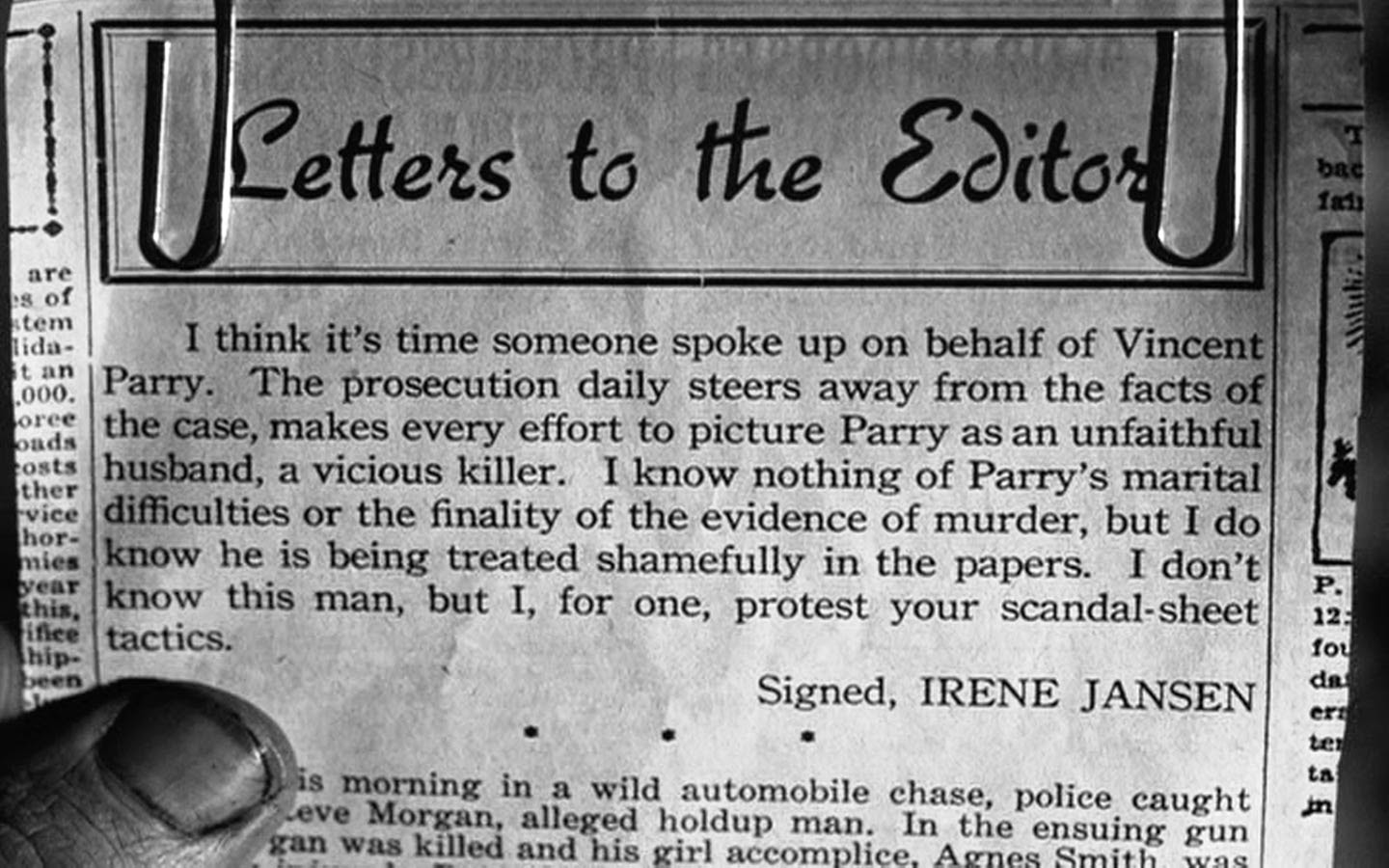

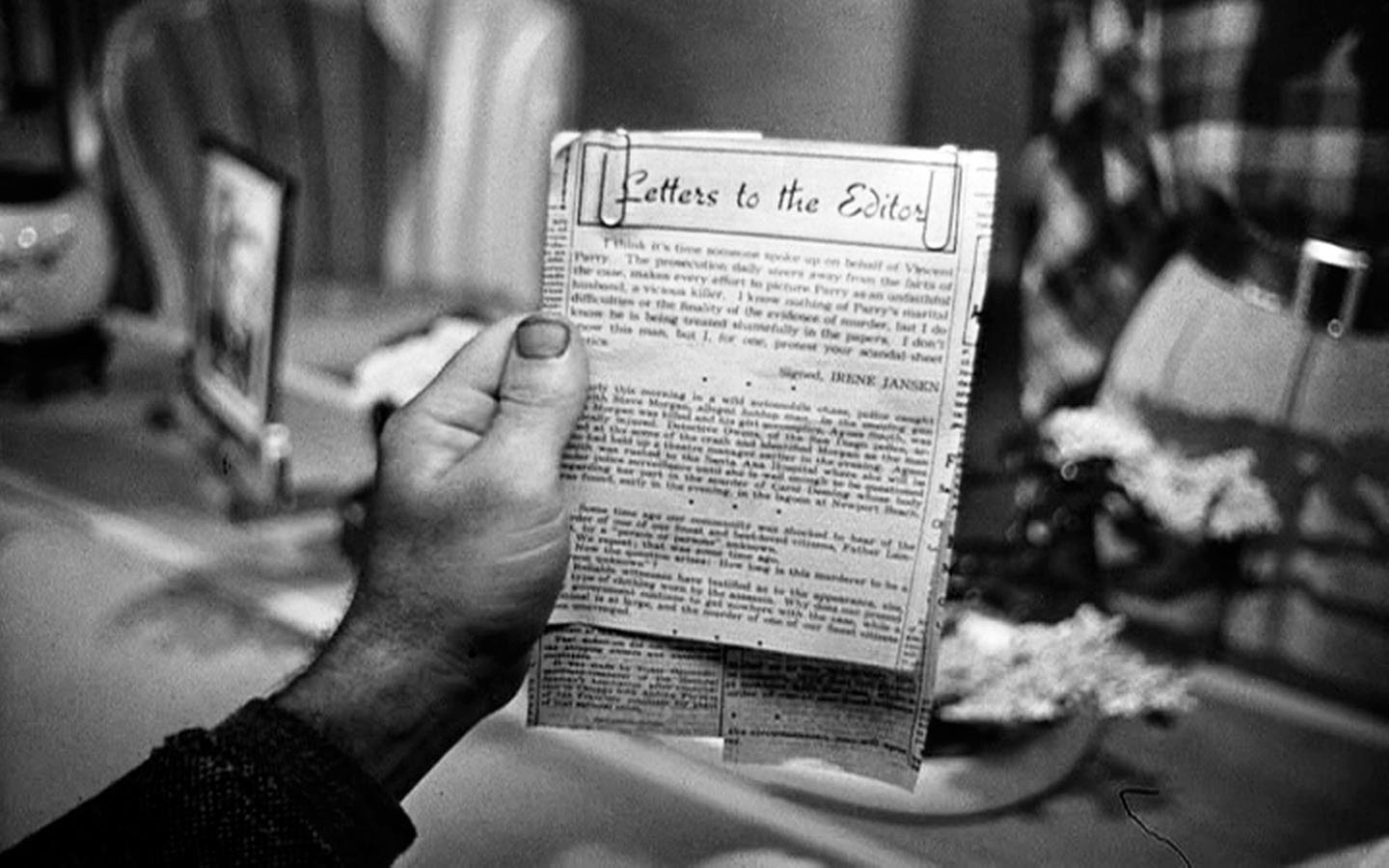

Irene's return to the room is shown when a rapid leftward pan conceals the cut to shot 3A. Irene walks toward Vincent, looking him in the eye (that is, looking right into the camera), then stops and hands him the newspaper clipping, which Vincent accepts and looks at in shot 3B. Then, when Vincent begins to read aloud, there is a straight cut to shot 4, a close-up of the clipping which shows Irene's letter to the editor. This instant change of framing, which does not indicate a lapse in time, is another violation Vincent's fluid point-of-view.

After Vincent reads the second sentence, there is a straight cut to shot 5, the most problematic shot of the sequence. It begins with Irene looking down, listening as Vincent reads. At one point, however, she looks up, directly into the camera. In

Dark Passage, to look at the camera is to look Vincent in the eye, but we know that Vincent can not be looking back to see Irene looking at him, because his eyes are on the newspaper clipping that he is reading aloud. Furthermore, we know from Irene's placement in shot 3B that she is standing face-to-face with Vincent, but shot 5 is from an angle to Vincent's right. Her look into the camera, then, could not be at Vincent's eyes. This shot therefore creates the illusion of being Vincent's point-of-view, even though it is not. (Or perhaps the illusion excuses her look into the camera — this could have been a cheat shot inserted during editing, though the effect it has is confusing.)

Another straight cut to shot 6A brings us back to almost the same framing as shot 3B. The rest of the sequence plays out in this shot, with the movement of the camera/Vincent's eyes motivated by narrative elements: the ringing telephone (6C), Irene talking on the phone (6D), Irene walking back to her position behind the table (6E), Irene sitting at her desk (6F), and Irene standing and gathering her things (6G). As in the previous example in Baker's car, Vincent's eyes are constantly trained on Irene or other important elements; there is no stray camera movement to simulate wandering eyes.

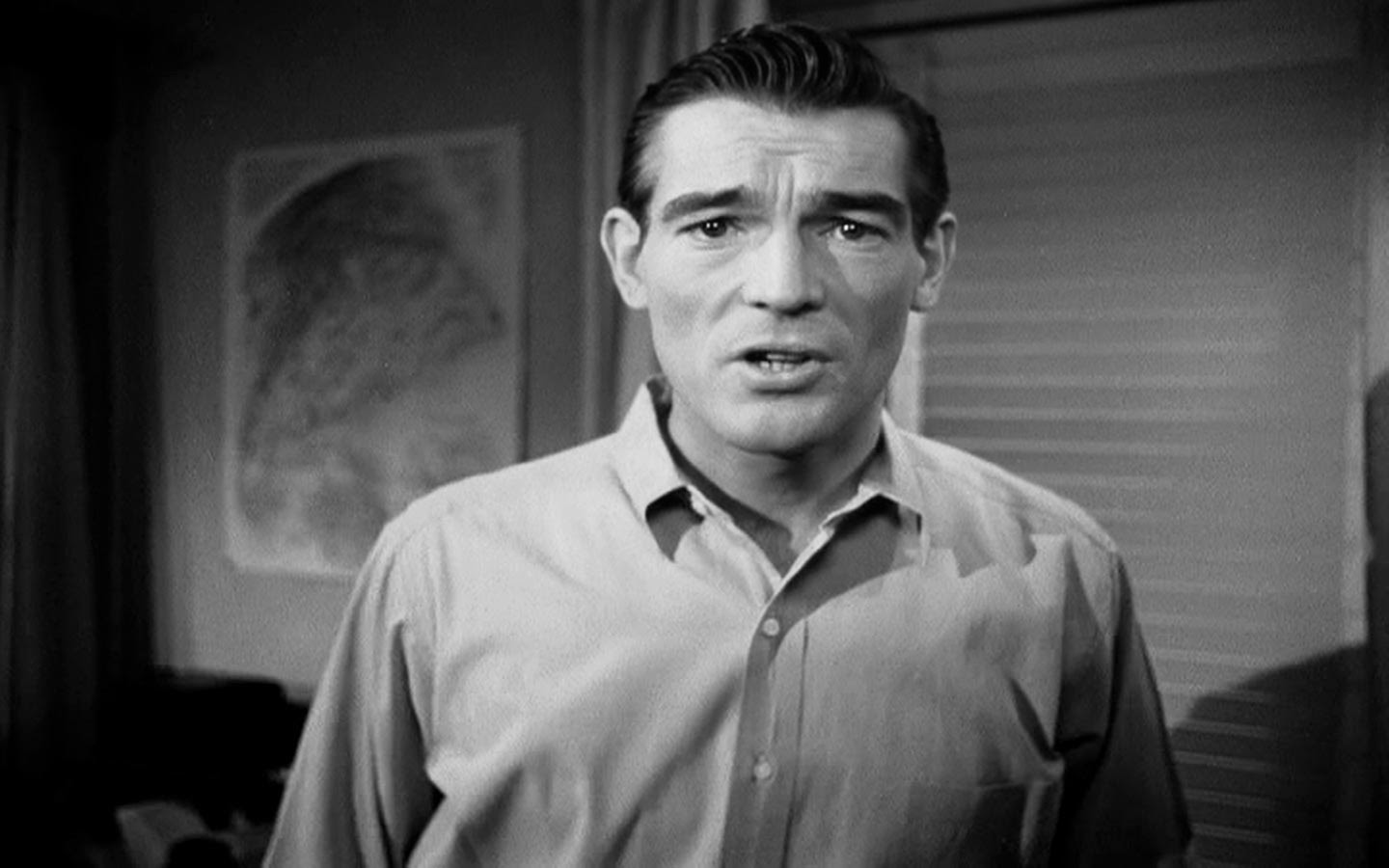

George's apartment

The first scene in George's apartment is comprised of seven shots. All but the first three or four (depending upon how you consider shot 4) are from Vincent's point-of-view. What makes this sequence interesting is that all shots are joined by straight cuts which, in the case of the point-of-view shots, violate the consistency of Vincent's point-of-view.

|

| 1 |

|

|

| 2A |

|

|

| 2B |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5A |

|

|

| 5B |

|

|

| 5C |

|

|

| 5D |

|

|

| 5E |

|

|

| 5F |

|

|

| 6A |

|

|

| 6B |

|

|

| 6C |

|

|

| 6D |

|

|

| 6E |

|

|

| 6F |

|

|

| 6G |

|

|

| 7A |

|

|

| 7B |

|

|

| 7B dissolve |

|

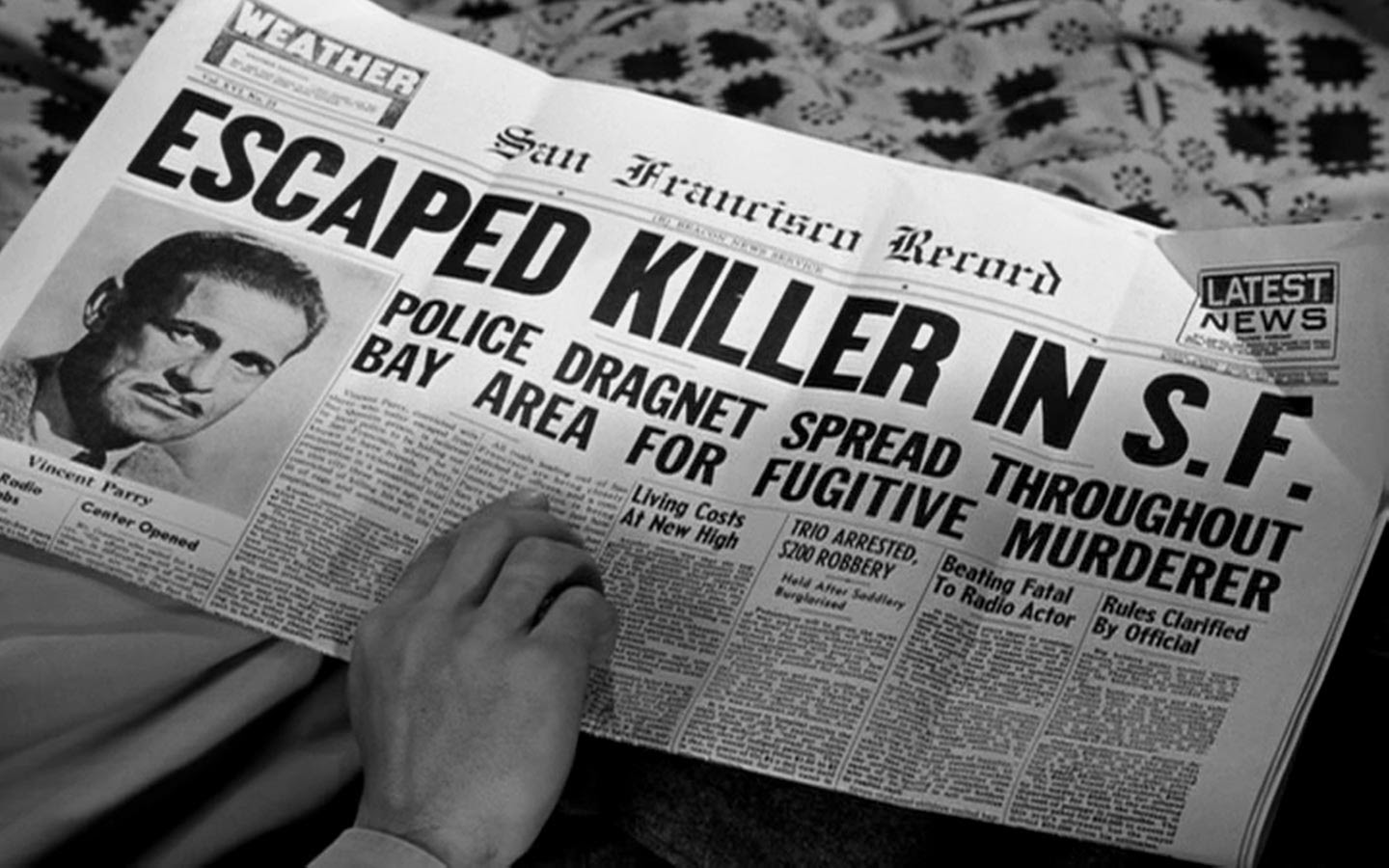

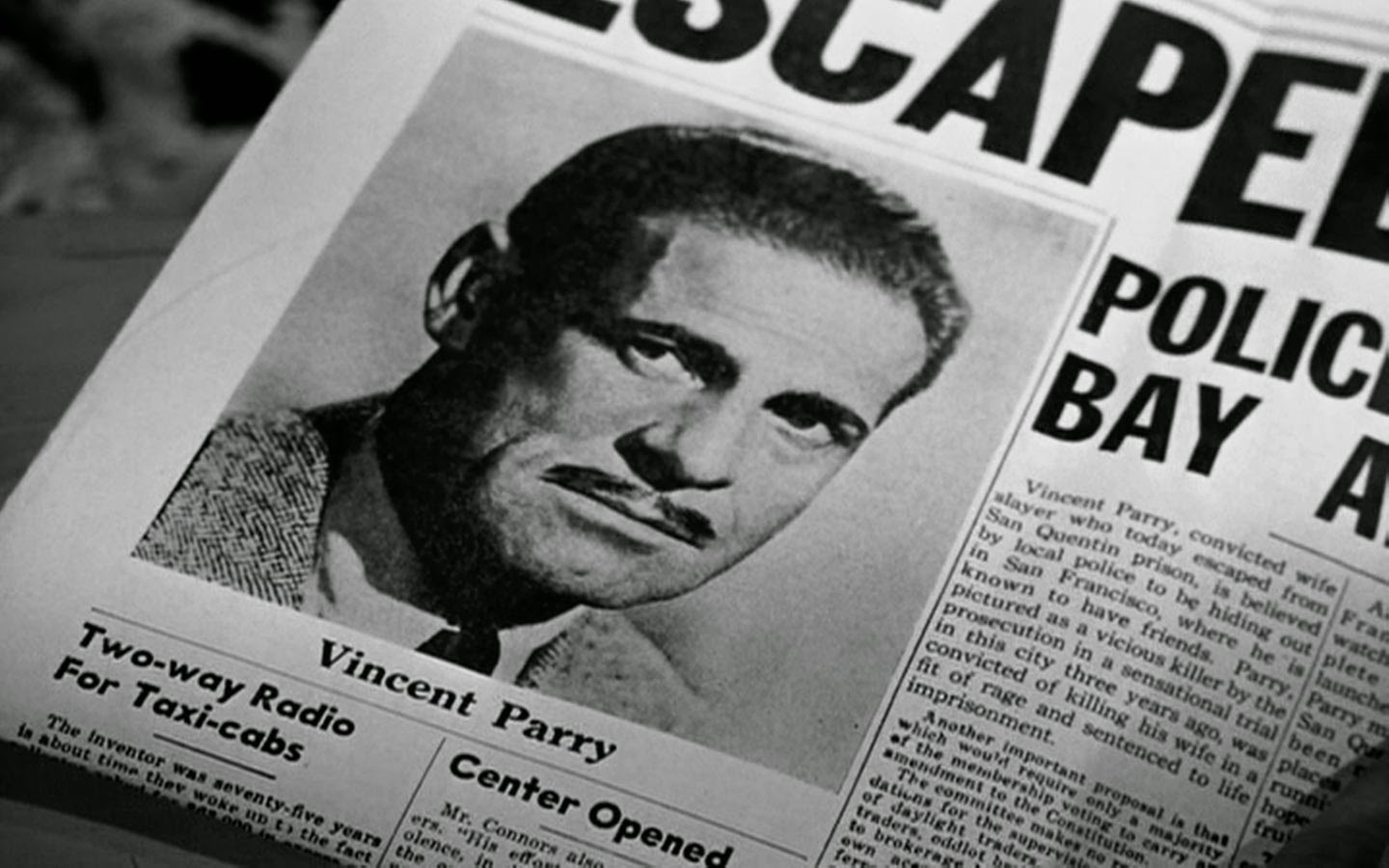

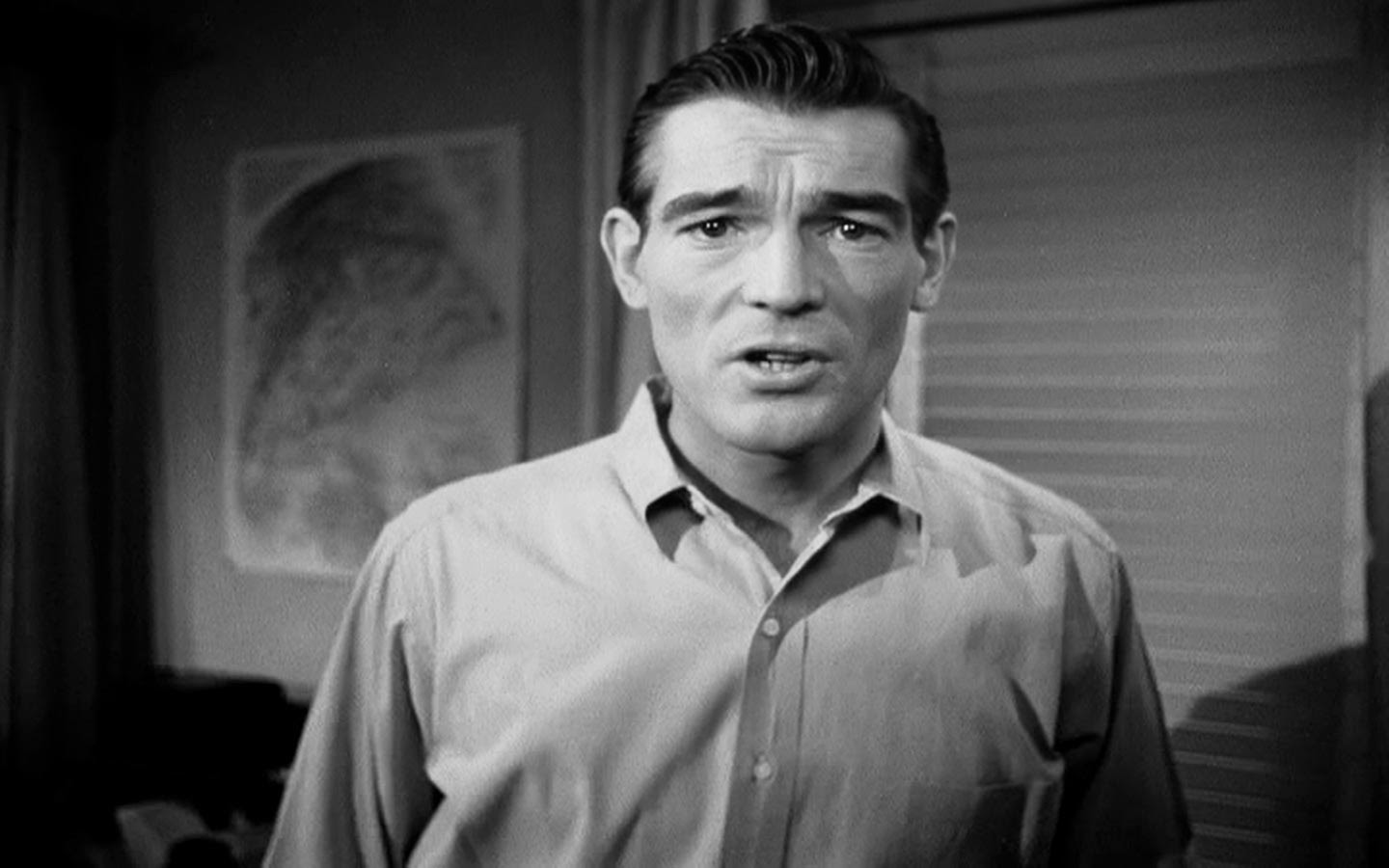

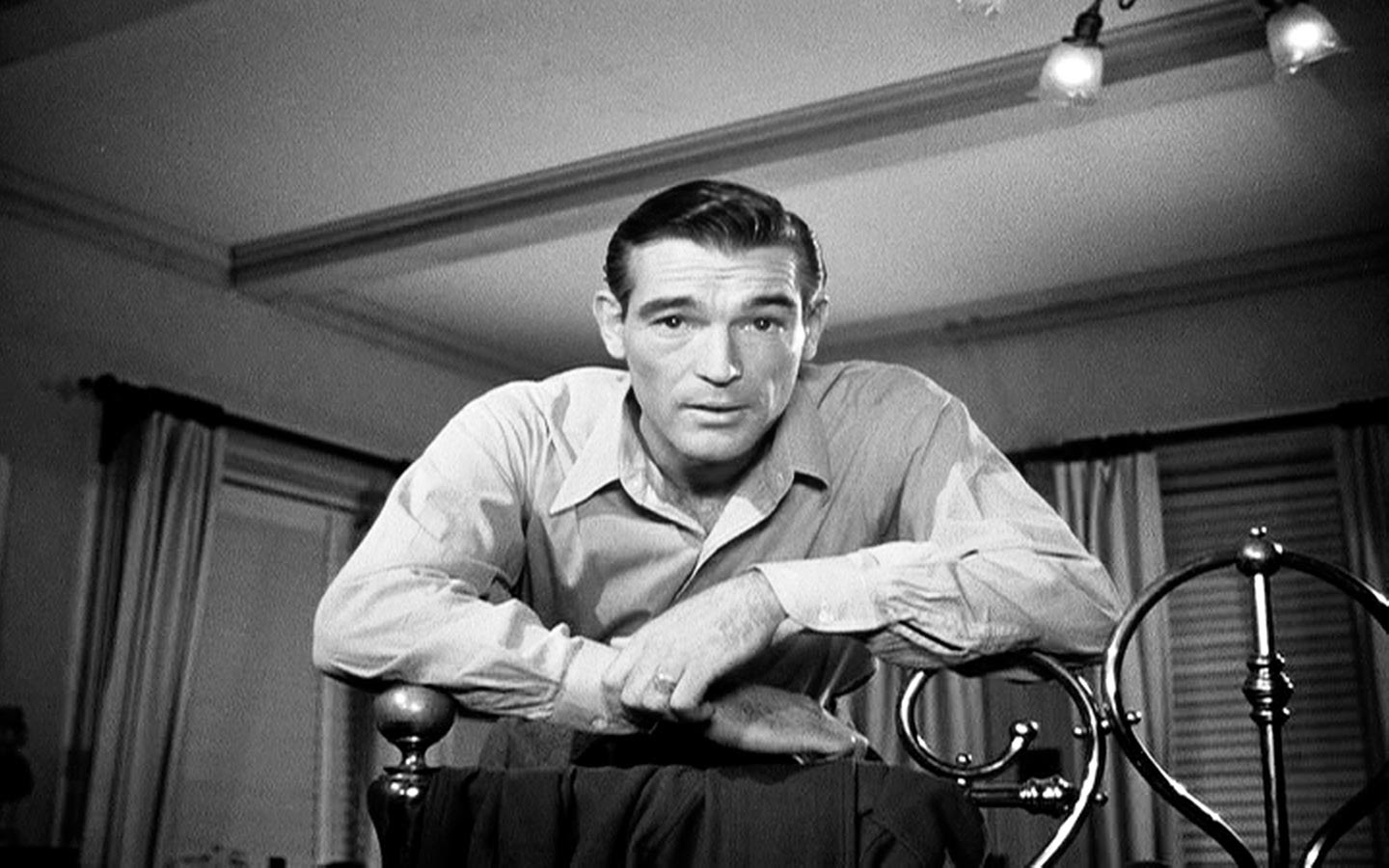

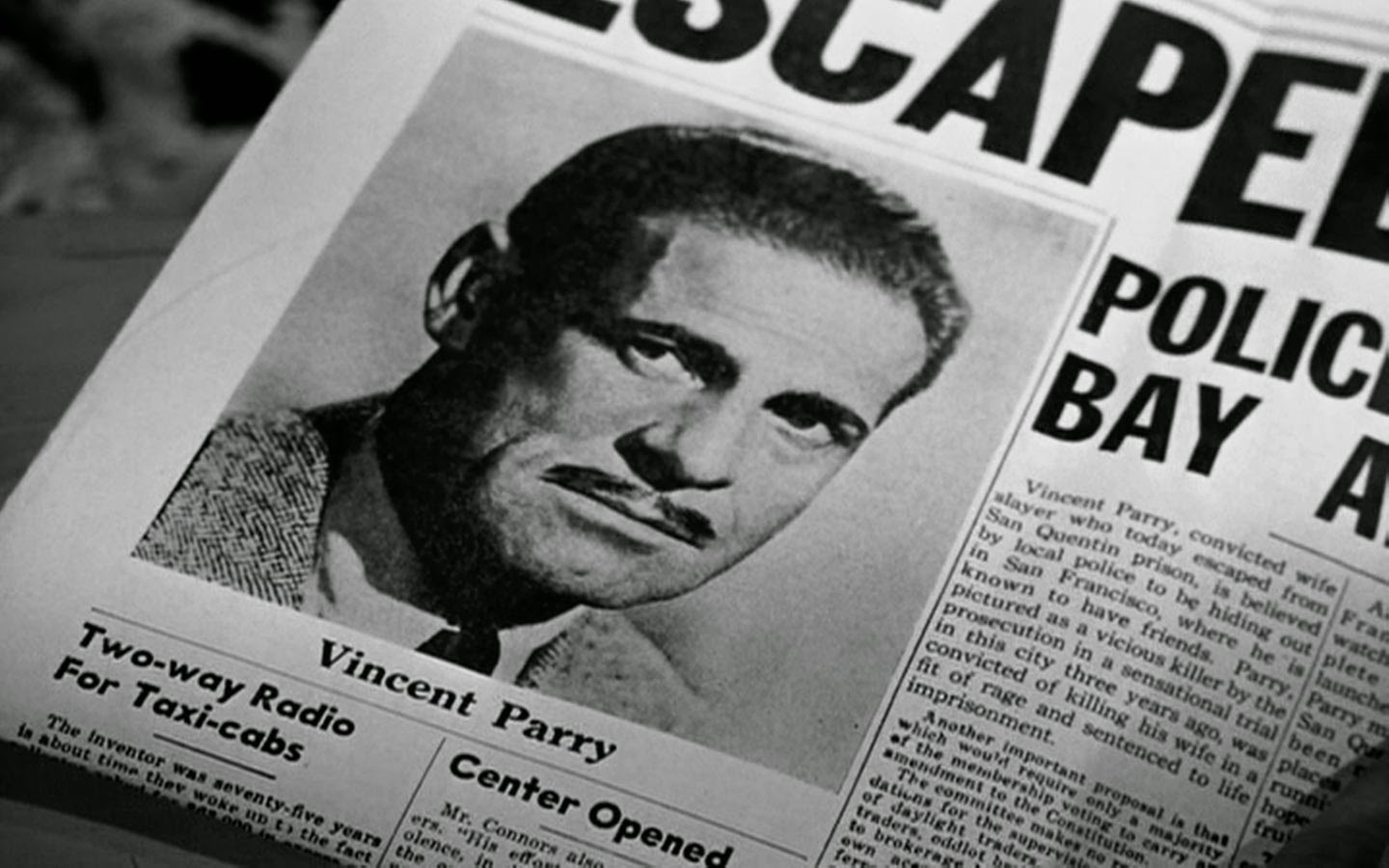

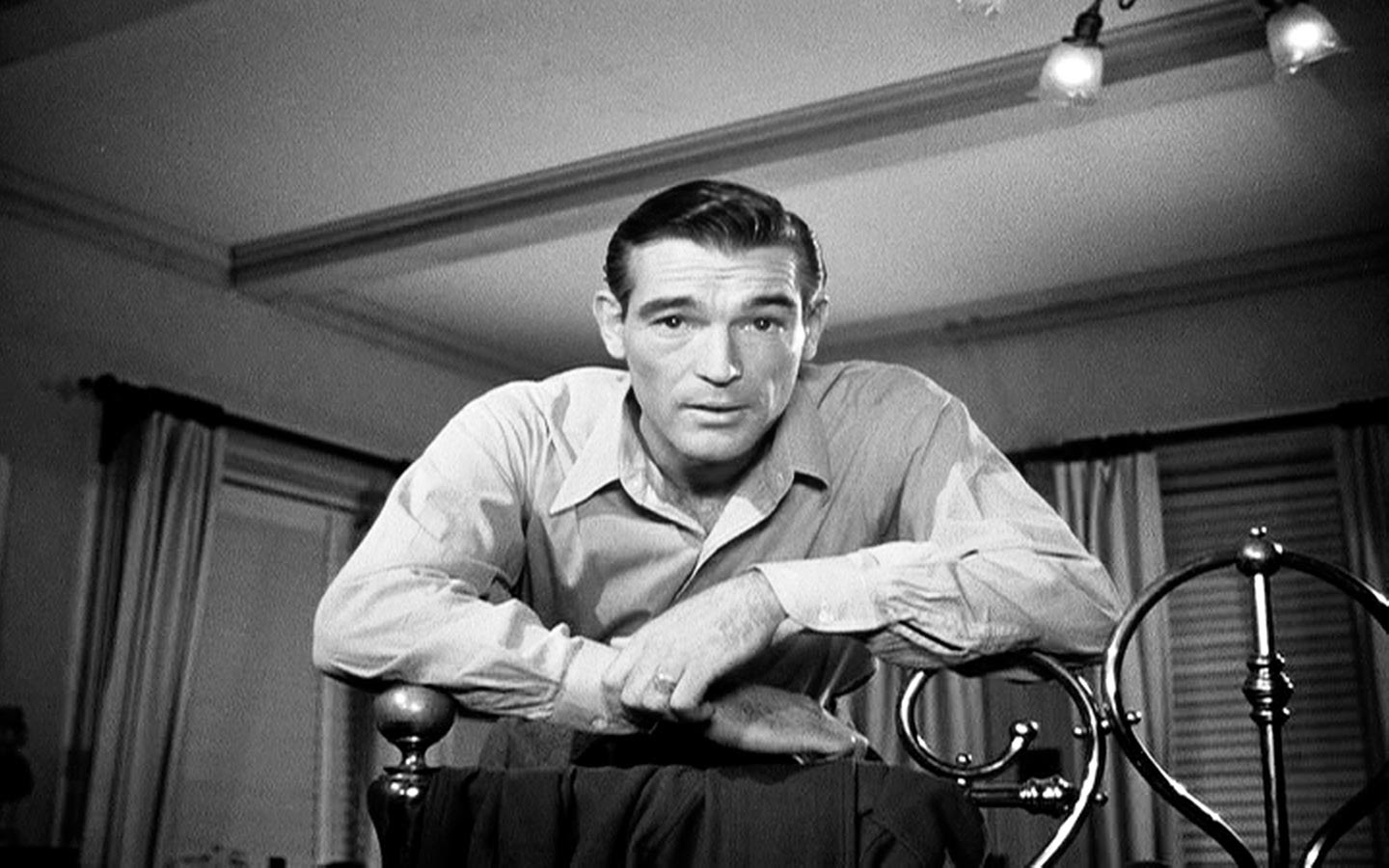

The sequence opens with a shot of George sleeping on his bed, then cuts to the newspaper on his chest which bears a headline about Vincent's escape. This omniscient point-of-view occurs regularly in the film, even in the first 37 minutes. We switch to Vincent's point-of-view perhaps at shot 4, which is a close-up of Vincent's thumb ringing the doorbell. This may or may not be Vincent's actual point-of-view. It seems unlikely, given the tight framing and the angle from which it is shot, but certainly Vincent's point-of-view beings by shot 5A, when George opens the door and looks directly at Vincent/the camera. If we consider shot 4 the start of Vincent's point-of-view, then the cut to shot 5 instantly changes Vincent's perspective without using camera movement as a transition.

Shot 5 continues, with camera movement motivated by George — each time he moves to a different part of the room, Vincent's eyes follow and the camera reframes the shot. It's at the cut to shot 6 that we get the first serious violation of the fluid presentation of Vincent's point-of-view. In shot 5F, George opens a drawer at the head of his bed to get a key for Vincent while Vincent is seated at the foot of the bed. The cut to shot 6A reframes George and the drawer in a medium close-up, from a much different angle, but matches George's action with the keys in the previous shot. When Vincent's hand appears from behind camera right, we see that this shot is also Vincent's point-of-view, indicating an immediate change in Vincent's position on the bed. George's dialog gives some justification for this — right before Vincent reaches for the key, George says, "Lie down Vince, and make yourself at home," possibly suggesting Vincent's change of position is due to his lying down, though offering no explanation for the speed at which Vincent is able to do so. Another equally abrupt transition occurs in the cut to shot 7, where Vincent is instantly repositioned further down the bed, looking at George from a higher angle, apparently standing up once again.

The end of point-of-view: the "coming-to" shot

|

| Vincent goes under |

|

|

Vincent's hallucination

(excerpt) |

|

|

Vincent's hallucination

(excerpt) |

|

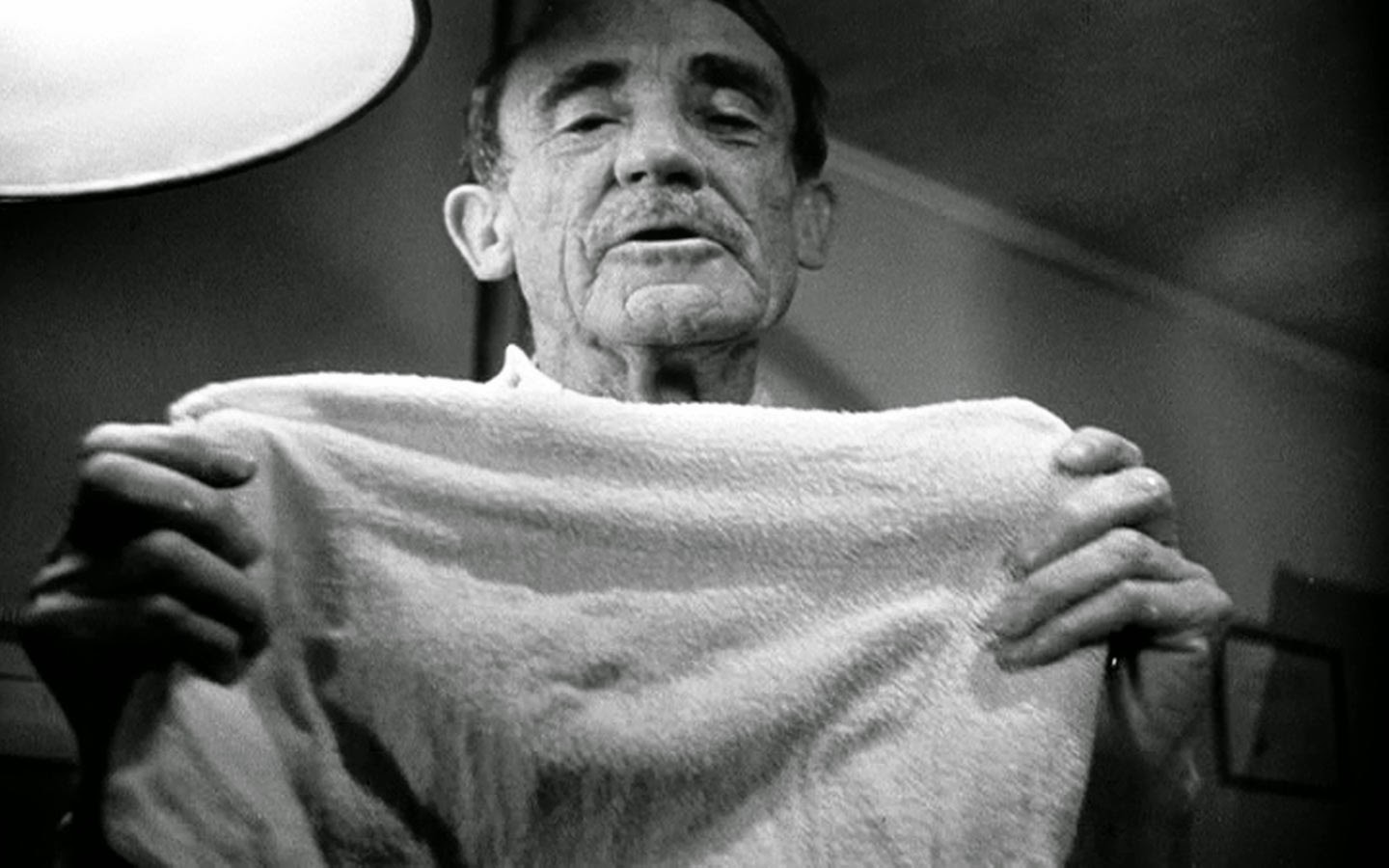

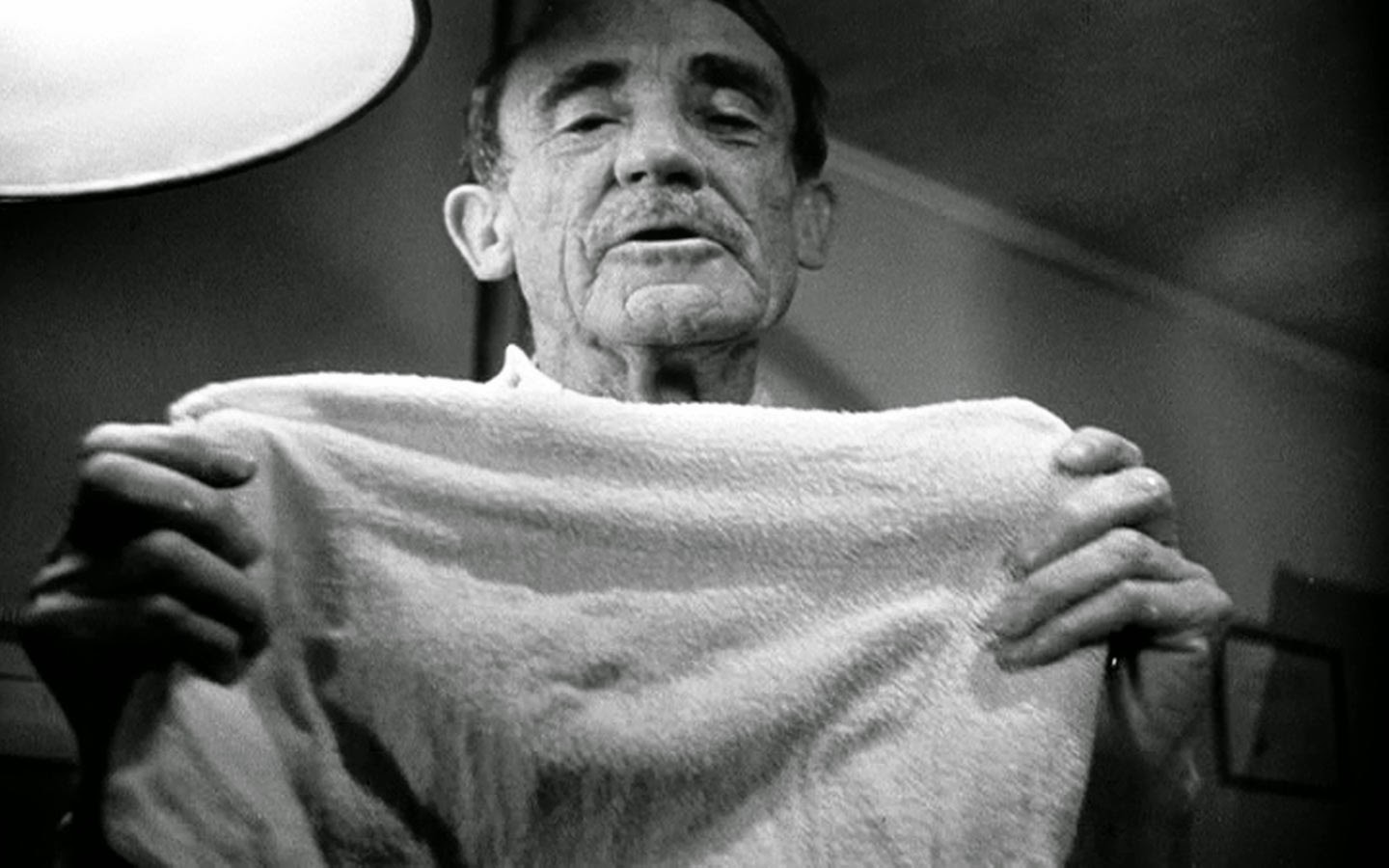

The surgery scene is the last one to feature such extensive use of Vincent's point-of-view. We watch the moments before surgery through Vincent's eyes, up to when the surgeon covers Vincent's face with the wet cloth. We then see what could be called Vincent's "psychological" point-of-view in the form of the anesthesia-induced hallucination he experiences during the surgery. This hallucination fades to black, and is immediately followed by what I call a "coming-to" shot.

|

| The "coming-to" shot, part 1 |

|

|

| The "coming-to" shot, part 2 |

|

|

| The "coming-to's" reverse shot |

|

I have

written about the "coming-to" shot before; it is used to show a person regaining consciousness and typically shows one or more people shot from a low angle, looking down, entirely out-of-focus, suggesting that we are looking through the eyes of a person coming-to as others look on. As the shot comes slowly into focus, however, we see that the people in the shot are not looking into the camera lens, but off to the side, exposing the shot as not truly subjective. As Vincent comes to, the surgeon and Sam, the cabbie, looking down at him, come into focus, and we ultimately see that they are not looking at the camera, but off camera left. The next shot is from over their shoulders, of Vincent's bandaged face looking up at them. This traditional technique is perhaps fitting, as it marks the point where Vincent's point-of-view stops being used so extensively and the film reverts to more traditional methods.

Notes

1I am not considering such concealed edits a violation of Vincent's POV, because in most cases they function to create the illusion of an uninterrupted point-of-view shot by extending a shot that would otherwise need to end (due to the finite amount of film in the camera or on-set restrictions on camera movement) or by creating a unified cinematic space from different shooting locations.

2In this case, I am certain that no time has lapsed, though uninterrupted conversation is not always an indication of temporal consistency — see Rachael's Voight-Kampff test in Blade Runner, e.g.

3Something else not indicated here, or in the majority of cinema's true point-of-view shots, is blinking.

4Indeed, any aimless camera movement would not fit in among the rest, which appear to always be motivated by something, whether immediately obvious (like Baker's question about the wet shoes in shot 2B) or not (like the pan from shot 5B to 5C which reveals the distinctive seat cover, which will tip Vincent to Baker's presence later).